The Crombie brothers with their father

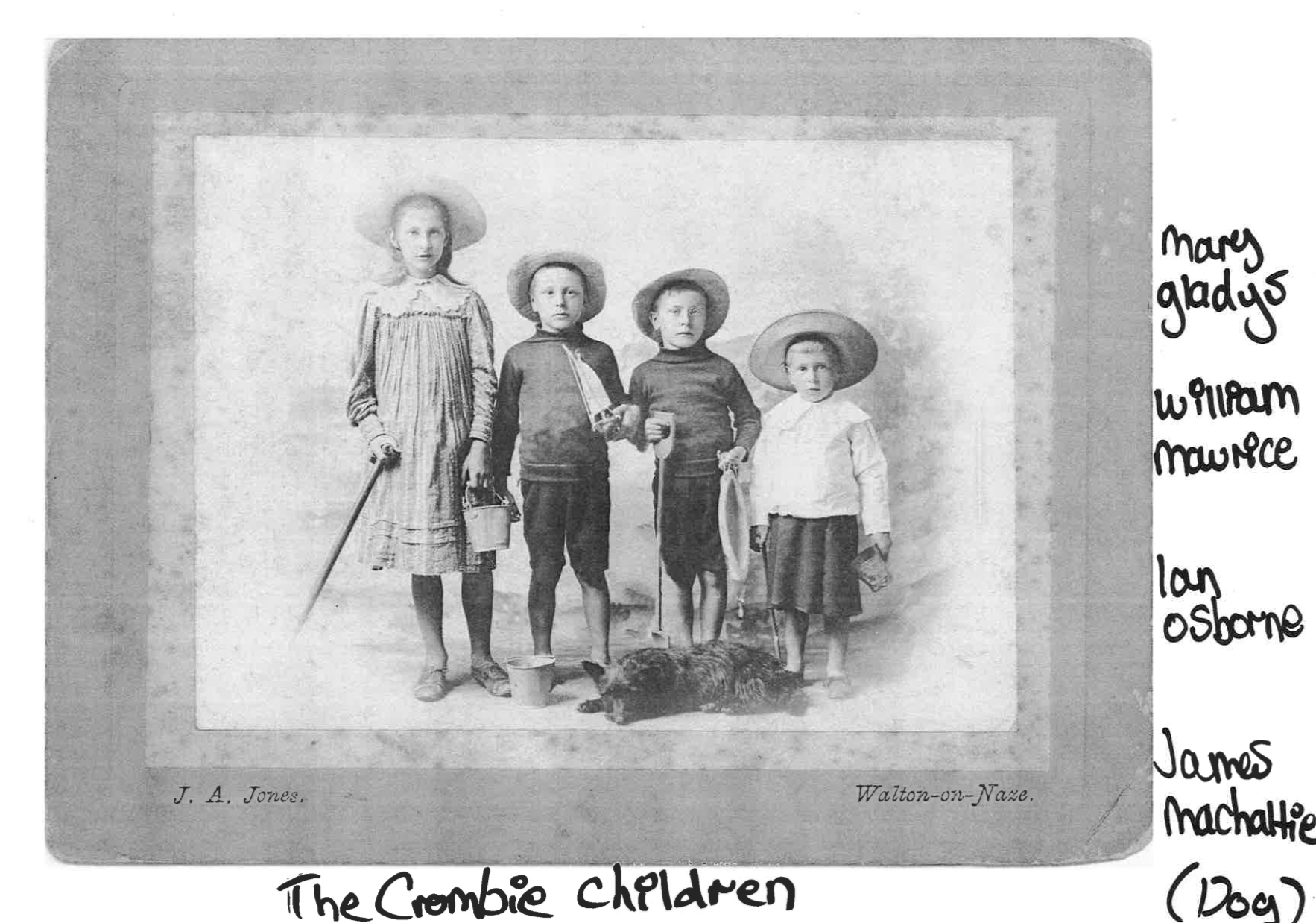

The Crombie brothers: Captain William Maurice, Captain Ian Osborne, and Second Lieutenant James Machattie

Dan Hill’s research, edited by Ellie Grigsby

William Maurice Crombie

Perhaps the most acknowledged, defining experience and emotion of the entire First World War was the universality of bereavement. With a special, and devastating impact on mothers, the heart-ache was felt across Europe and the wider world. One family: one grieving mother, who lost more in one generation than she would have ever dared to conceive the prospect of, was Mrs. Mary Crombie from Hatherley Road, Sidcup.

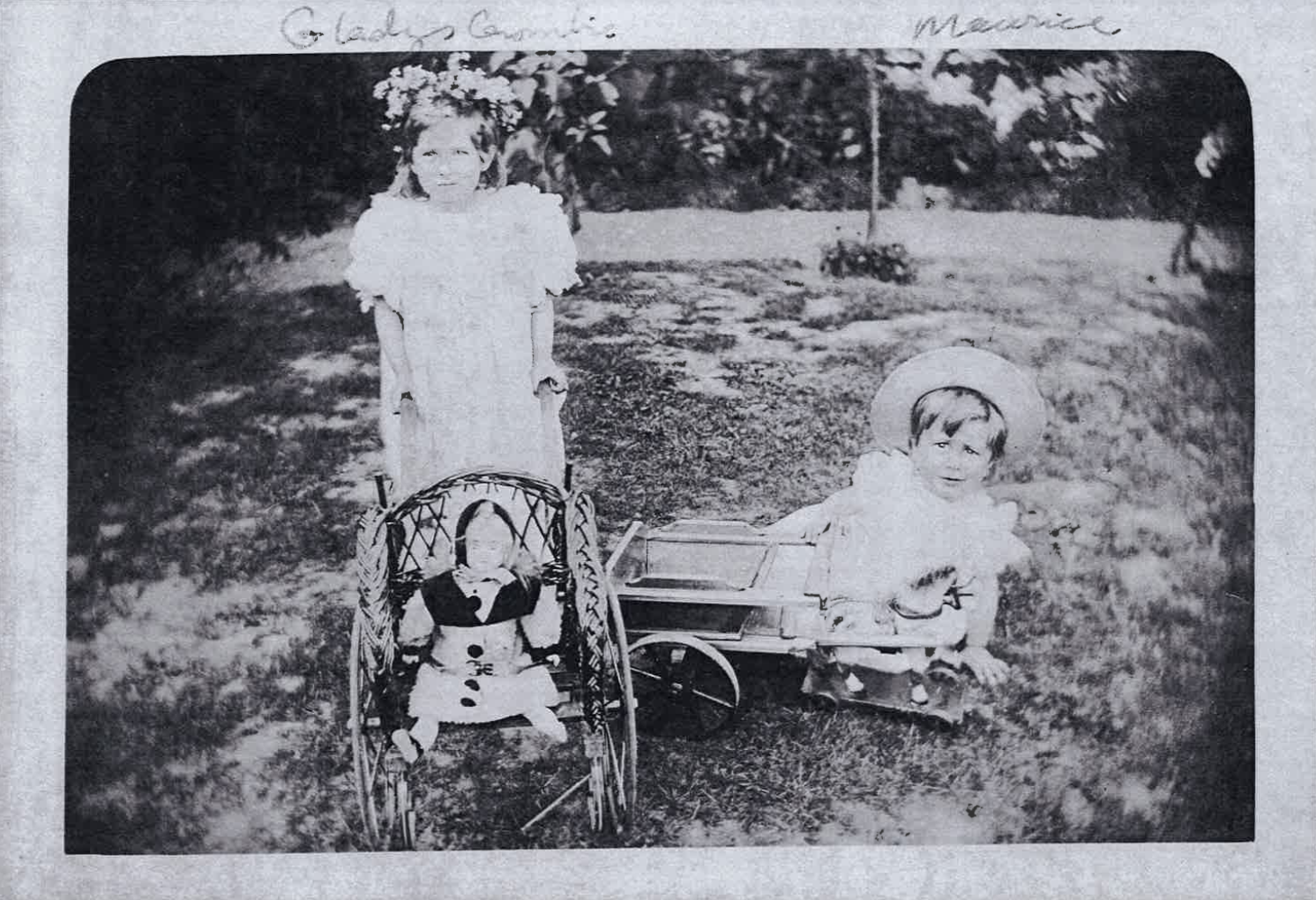

Mary Crombie and her husband James lead a financially comfortable life pre-war; Mr. Crombie by the time of his death was quite the pillar of local society. Crombie was a partner in his own medical practice of Crombie and Callender. His surgery was inside the confines of his grand 11-room home. Besides providing healthcare to the local community, in his lifetime, he was involved with local VAD hospitals, founded and was acting secretary of the Sidcup golf club, was once a president and secretary of Sidcup literary and scientific society, was involved with the work of the RSPCA and was chairman of the Footscray urban district council to name a few. James and Mary went on to have four children: Mary Gladys (born 1891), William Maurice (1893), Ian Osborne (1895), and James Machattie (1897). All three of their sons attended Merton Court Preparatory for their primary education with all three gaining scholarships to further their education. Both William Maurice (affectionately known as simply Maurice), and James, were awarded scholarships with Epsom college, where as the middle-born son Ian, went to St. Paul’s school (Ian was also a scholar of Wadham College, Oxford).

As The First World War erupted across the world stage it interrupted romance, education, professional careers, poverty, politics, social boundaries, friendships and kinship ties. The Crombie brothers abandoned their higher educational pursuits and careers as they rushed to colours.

In the Autumn of 1914, Maurice joined an ambulance unit connected to the 4th London Mounted Brigade and spent some months in Norfolk. By order of the War Office he went back to finish his medical course. After graduating from Epsom college, Crombie had progressed to St. Thomas’ hospital where he achieved several medical diplomas. By 1916, although still a young man at 23 years of age, Crombie held the position as senior obstetric house physician at the hospital and by May 22nd, he took a temporary lieutenant commission in the RAMC.

Whilst he was tending the sick and wounded, unable to think of anything else other than mending these young soldiers, pushed to his limits of endurance and mental strength, he was struck by the overwhelming news, his younger brother Ian Osborne had died at war.

We no longer have Crombie’s service record file, which was most likely destroyed during the German bombing raids of the Second World War, so it is difficult to geographically locate Crombie throughout his wartime service nor ascertain every certain and important date. However, we know that in early 1917 he was actually in the United Kingdom. On the 20th January, Crombie took Grace Almora Frank’s hand in marriage. The two sweethearts were married at St. John’s Church, Sidcup. Unusually, Grace was 31 years of age when marrying a 23-year-old Crombie. Whilst not particularly rare today, at the turn of the century this would have been considered taboo. Just three days after his marriage, the blissful whirlwind of being newly-weds in an era of uncertainty was predictably interrupted as Crombie was transferred from the RAMC to the Indian Medical Service (IMS) in Karachi where British and Indian soldiers were fighting the Ottoman forces until he was transferred to Baghdad.

As Crombie was digesting how much his life had changed during war: he had made a life-long covenant to his sweetheart, obtained a higher paid war-work placement through promotion with increase in social standing, and lost a brother, his life was to succumb to a further tragic modification once more and not for the last time. Crombie, lost his other brother James Machattie to the war on July 2nd, 1917. Crombie now bearing the heaviest of hearts no doubt feeling grief throb through his veins, had to continue his contribution to the war-effort; the very war that took both of his young brothers. It is probable William Maurice felt an amplified sense of dedication and determination because of this. Succeeding his position as temporary lieutenant, Crombie was appointed a permanent position as lieutenant in the IMS.

On December 14th, 1917, the walls of number 20 Hatherley road, heard a new kind of cry that wasn’t induced by grief and sorrow. Grace, gave birth to a child. It is touching that the infant was named ‘Ian Machattie,’ in honour of his late brothers, posthumously keeping their names alive, embodied through who would have been their first baby nephew. Providing Grace’s baby was full-term (as it would be unlikely an exceedingly premature baby would have survived in 1917), we know Crombie must have been granted home leave after marriage in January once more as least, early April. As Ian Machattie reached the tender age of nearly four months old, as a new life grew, Crombie had to say goodbye to one more. Crombie lost his father on March 30th, 1918. Authors of the Sidcup and Lamorbey history society’s ‘Sidcup’s home front in the Great War’ short informative brochure claim: ‘…the death of two of his sons, in 1916 and 1917 was seen by some as contributory to Dr Crombie’s early death.’ There is no question that Dr Crombie could have died from the heart ache, leaving his only surviving son behind now riddled with sorrow, to negotiate the loss of his father, and two young brothers, all in consecutive years of each other.

Crombie would have spent his war service battling tropical diseases more than wounds inflicted by the enemy in-fact. Malaria was rife this side of the continent which plagued European officers and men of other ranks. Whilst tending to the sick and wounded, exposure to such deadly diseases was the core of Crombie’s war-work. It is therefore unsurprising that Crombie succumbed to a tropical disease himself, contracting the normally always fatal fever, Kala Azar, whilst serving in Baghdad. Initially, the parasites cause skin sores and ulcers, but once the disease progresses, it attacks the immune system. Crombie was consequentially invalided back to the UK for treatment. Crombie had almost recovered, when his weakened immune was overwhelmed and forced him to capitulate to the flu pandemic. Crombie died in Albert Dock hospital of tropical diseases on February 17th, 1919.

Crombie was laid to rest, several days later in Foots Cray cemetery. Leaving behind his mother, wife and son to hover around his grave-side forever absent of their son, husband and father. Grace never re-married, she died in Oxford in 1960, age 75.

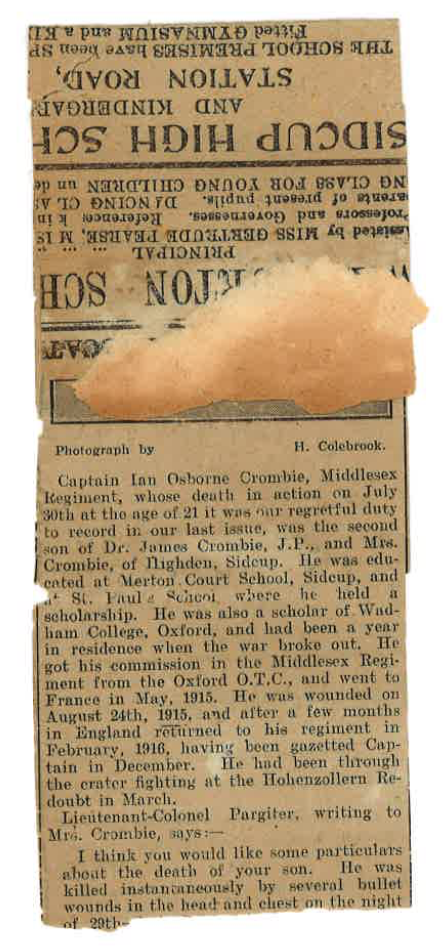

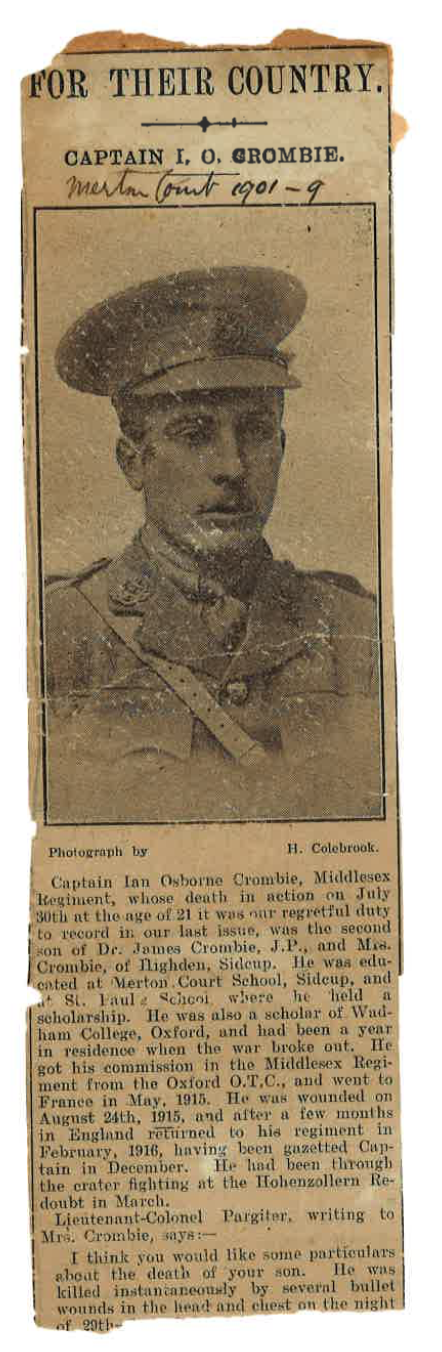

Ian Osbourne Crombie:

Ian had been at Wadham College, Oxford, for a year when the war broke out. Before this, Crombie was a scholar at St. Paul’s. Here, he was quite the celebrated athlete, and a pupil who was ‘depended on,’ described as the headmaster’s ‘ideal British school boy.’ The headmaster wrote about Crombie saying: ‘…he touched nothing without leaving his mark… his aim was to leave things (a) little better than he found them.’

Crombie was successful in obtaining a commission to the officer ranks, with records showing he joined the 11th battalion of the Duke of Cambridge’s Own Middlesex Regiment. This battalion, of around 1000 officer and men of other ranks was raised entirely of volunteers with a few officers and Non-Commissioned Officers (NCO’s) integrated into its ranks who had previously seen service. Crombie and his men were trained in Colchester, Shorncliffe and Aldershot during the early phase of 1915 until the battalion finally saw overseas service landing in Boulogne, France in June; but, without Crombie. It is undetermined as to why Crombie did not initially join his men as they sailed to France, perhaps he stayed behind to assist in training new recruits. By September, Crombie too had crossed the channel to join the men of his battalion. Dates appear muddled when cross referencing certain sources from the remnants we have of his war-time service, but what is important is that it is recorded Crombie was wounded in 1915 at least twice. Supposedly returning to his regiment in the early months of 1916 after some convalescence at home in England, Crombie returned to his regiment, a Captain, having been appointed the new rank in December. The details we have of Crombie’s twice wounding (unfortunately without dates) tell of his gallantry which was argued as a reflection of his innate character, as Crombie, suffering from a broken arm, went around the battlefields after his men had retired to see no tool was left behind. Secondly, it is said Crombie was the victim of a choking and terrifying gas attack as he strived to save some engineers from the result of a back fire from a mine.

By 1916, Crombie had experienced his first months of industrial warfare and those early months of 1916 came attached with a feeling of suspicion, as Ian and his men begun to hear rumours of a plan to move southward where the British had taken over a new sector of the frontlines from their French Allie; an area named for then main river than ran through the region; the Somme.

As 120,000 soldiers lined up ready to attack on 1st July 1916, Crombie and his men (now in charge of around 180 men in B Company of the Middlesex Regiment) found themselves behind the lines, reserved and waiting in readiness to exploit by infiltration any successful punctures in the German lines, achieved on that first day. The British bombardment on that morning, today remains the worst day in British military history; around 60,000 men were taken as wounded or dead, with an estimate of just short of 20,000 fatalities, whilst gaining a pathetic three-square mile of territory.

Using the battalion’s war diary for coverage of early July we can ascertain rich imagery of Crombie’s actions on the 7th July 1916. The diarist introduces us to the events of this very day at 15:00pm with the vivid story of a Captain Lewis shooting ‘one German’ with a rifle and was then killed himself by a rifle shot from the front. After Lewis’ death, a Captain Moore, resumed command, and after a bombing post was established with a Lewis gun on his right, the mission to capture the German trenches pursued. By 19:45pm, B Coy, under command of Captain Crombie, a Lieutenant Shaw and 2nd Lieutenant Tatham with fifty men of other ranks, managed to cross and cease the trenches without being fired on. This was seemingly due to the protective firing barrage that covered the soldiers as they advanced. After capturing the German trenches, a retaliation attack at 4am on the morning of the 8th seemed imminent. Captain Crombie placed a Lewis gun in readiness as it was believed that German parties were seen to be carrying up bombs, yet it appears, no counter attack followed. After losing 50 men killed or wounded, Ian and all of his battalion were relieved from the front on the 8th by around 22:00pm. Awarded time to recuperate, the battalion were warned of an attack at the end of the month.

On the 27th July 1916, the 11th Middlesex Regiment were positioned on the new front-lines, this time, in newly captured German positions outside of the small village of Pozieres. These trenches Ian and his men were tasked with holding, were in a critical condition: after intense fighting for a long duration for possession of the village, this bitterly took an effect on the trenches that were now in an incredibly poor condition. It was even reported in the battalion war diary that the conditions were so bad that ‘in some cases it was difficult to (even) recognise the trench…’ Owing to the dire condition of the territory, and even the ‘predecessors (to the 11th battalion) having little knowledge of their dispositions, the relief was reportedly ‘extremely unsatisfactory.’ Some men actually went in the wrong direction, resulting in heavy casualties. The generally ‘vague’ and ‘scanty’ information the relief parties were holding on to was nothing but dangerous.

The following day, Crombie’s battalion were attacked in their positions by German soldiers who were desperate to retrieve their trenches by removing the enemy from the newly captured territory. During this time, the men of B Company worked hard to re-build the remnants of the crumbling trenches against the waging German attack.

On the morning of July 30th, 1916, Captain Crombie left his own trench to climb onto the rear side of it, his task: to make a ‘distinctive mark’ for ‘friendly’ observers. As a gentleman of distinguished rank, this job was not mandatory, nor in his remit; yet Crombie evidently felt capable and passionate about camaraderie and pulling together as a collective despite the detrimental risk he was taking, not officially required of him. As well as knowing where the enemy was, it was crucial for the higher command to know where their own soldiers for. Thus, this often entailed, leaving a trench and making an identifying mark on the ‘friendly side’ so that observers behind the lines/aircraft, could identify which trenches were held by their own men.

As he stood at the rear of his trench, attempting to undertake his mission, he was shot dead. After his death, Crombie’s body was removed from the front-lines and he was buried in the nearby cemetery at Bouzincourt where he remains today, alongside 481 bodies of men that left home for war, but never returned. His mother, was written to, given the details of her son’s death. Lieutenant Colonel Pargiter wrote:

“I think you would like some particulars about the death of your son. He was killed instantaneously by several bullet wounds in the head and chest on the night of the 29-30th July. The exact time was 01:30am on the 30th July. He was engaged at the time in putting up a mark on the parapet of the trench his company was holding. He was a great loss to me and to the whole battalion. He as a very excellent officer and a valued companion. Will you please (accept) my sympathy in your loss, and that of the whole battalion. We have buried your son in the Military Cemetery at __, very near the grave of Captain Lewis. A cross will be put up very shortly- Killed in action on Friday, 28th July 1916, age 21.”

After his death, Mary Crombie could no longer hold her son, all that remained were these words. After Ian’s death, his personal belongings were posted to his father: a collection of material objects touched by a war that took their son.

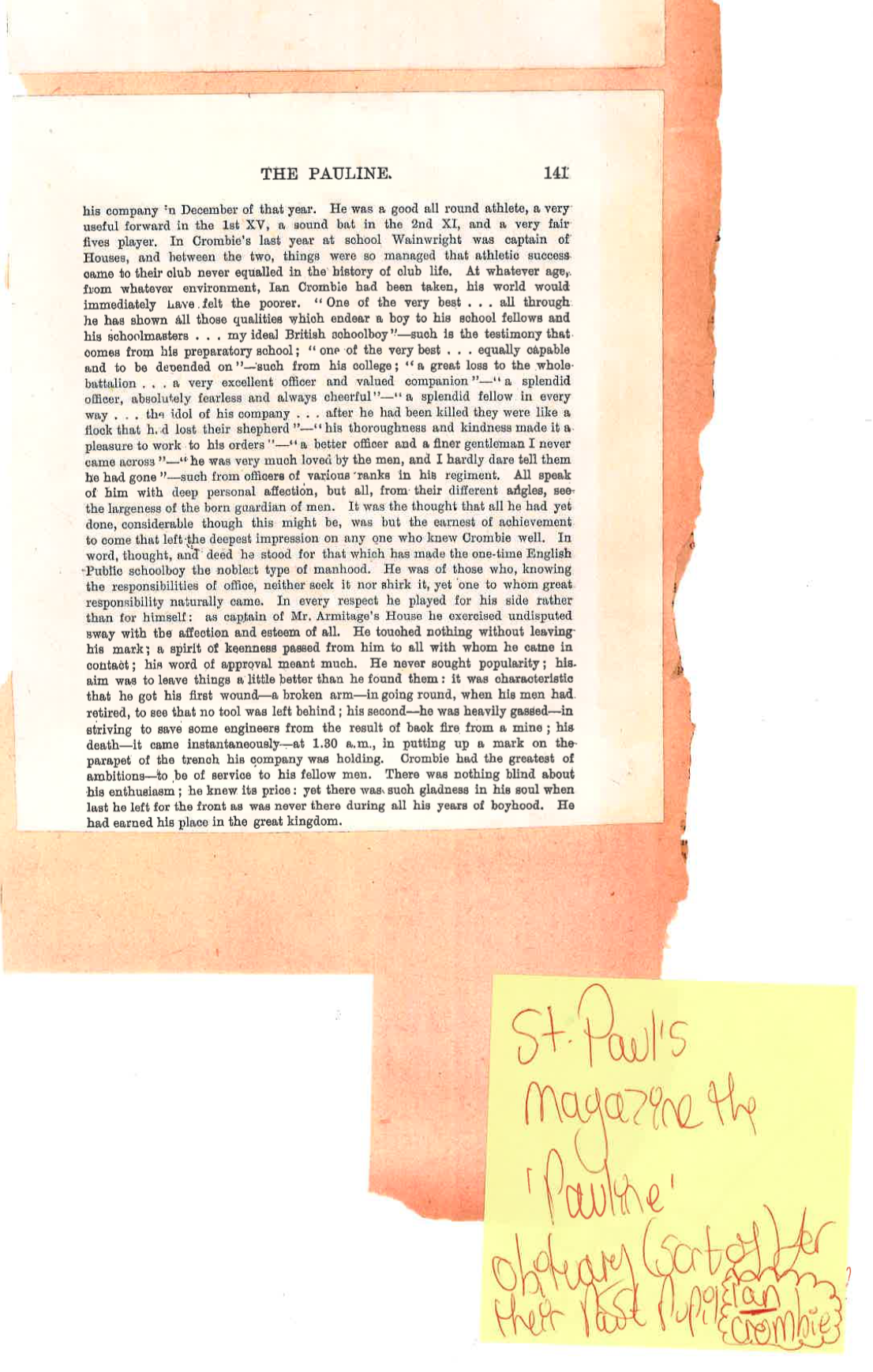

The Pauline, the St. Paul’s magazine printed an obituary to the late Crombie concluding: ‘at whatever age, from whatever environment, Ian Crombie had been taken, his world would immediately have felt poorer.’

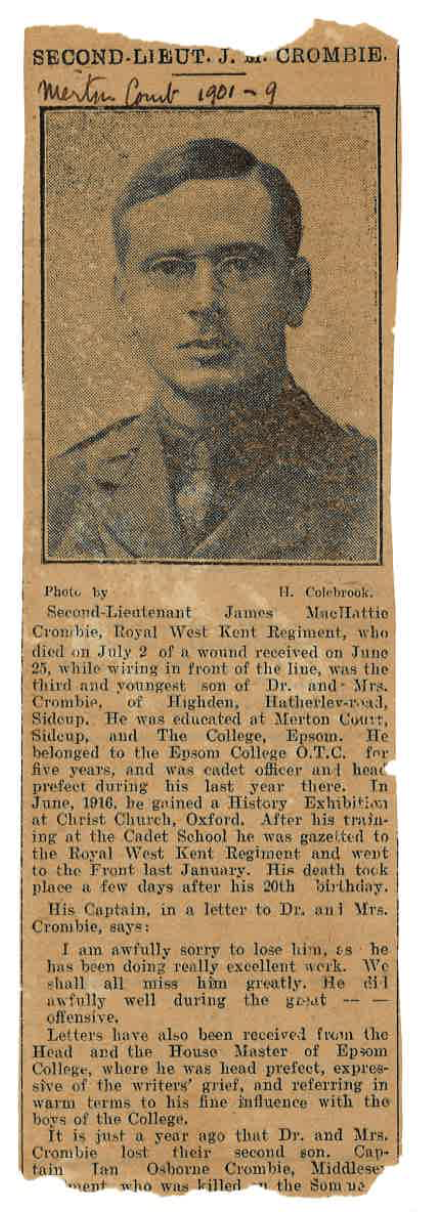

James Machattie Crombie:

James’ educational years spent at Epsom college, left behind a glowing impression. An article appeared in the ‘Epsomian’ school magazine in 1917 glorifying not only his academic achievements but his quality of character. We are given the briefest of overview of Crombie from 1911-1916 which is useful despite its lack of longevity when cramming down half a decade of Crombie’s young life. Crombie entered the college as a scholar in 1911, two years later he was made a prefect, whilst being charged with an element of pastoral care over his younger fellow pupils. By 1915, Crombie was appointed head prefect and captain of the rugby team. Crombie was described as an ‘incalculable assistance,’ in many aspects of Epsomian life; especially for leading the rugby team to victory for the shield and ‘inspiring’ others through example, notably of his impressive gymnast ability. Crombie was awarded a history exhibition at Christ Church, and for his success he was awarded the Armstrong Scholarship, but Oxford was not to see him. Crombie had obtained certificate ‘A’ in 1914 and became Cadet officer the following year. James, the youngest of the three boys would have just fell short of the required age as war broke out in 1914, and so watching his brothers sign up and join the war effort whilst he was maturing into a young adult reminds one of the fascinating George Orwell observation:

‘…As the war fell back into the past, my particular generation, those who had been ‘just too young,’ became conscious of the vastness of the experience they had missed. You felt yourself a little less than a man, because you had missed it.’

By August 1916, Crombie was training in Ayrshire, and eventually gazetted to a commission in the Royal West Kent (RWK) Regiment. It was during James’ final stages of officer training that he would have learned the devastating news that his older brother Ian Osborne had died whilst serving on the Somme.

Arriving in Flanders as Second Lieutenant Crombie with the 10th battalion of the RWK regiment in January 1917, the battalion were not initially involved in large scale attacks but spent months tackling the task of holding front-line positions on the Ypres Salient. Whilst in reserve lines, Crombie and his men were subject to intense and thorough training exercises. For Crombie this would have proved advantageous, allowing him a chance to adjust to life in a battle-zone: an entirely alien environment for such a young man, before fighting on the front. As the month of May drew to a close, perhaps rumours would have spread, that involvement in the upcoming battle at what we know as the notorious battle of Messines, was looming. By mid-May, Field Marshall Douglas Haig wanted to launch an attack in the summer which we know now as the third battle of Ypres, or Passchendaele. In order to do this, Messines Ridge, which ran to the south-side of the Ypres Salient, had to be captured first, otherwise, the attack further north could not be pursued. The battle of Messines is infamous for its element of mass mine detonation. During the battle, a series of underground explosive charges, secretly planted by allied tunnelling units beneath the German’s feet near the village of Messines in west Flanders. The mines were detonated at the start of the battle creating gigantic craters; the joint explosion of the series of mines, ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. Analysing the operational report of the 10th RWK regiment, its meticulous planning and pre-forward thinking is notable. It appears the role of Crombie and his battalion was support on the ground whilst continuing the advance to puncture and take the German line.

Following the successful attack at Messines, Crombie and the battalion were relieved from the front and allocated a period of 7 rest days to attempt to recuperate. By June 19th, the battalion were moving back up the line where they remained until June 30th. It is in this interim, that Crombie was fatally wounded. Frustratingly no official documentation of this wounding seems to have survived, besides, a torn newspaper exert featuring a short obituary of Crombie. In this, we can see it states Crombie was wounded on the 25th July which we hope is correct, but this is our only remaining narration of his wounding.

The operational orders for the 10th battalion, for the 23rd/24th of June stated the following:

“Patrol. O. C ‘B’ Coy will detail 1 officer or selected N.C.O and 20 picked men (including Lewis gun team as covering party) as a SUPPORT LINE by day and operate by night. Patrols on wire, and those to communicate with units on flank, will be found by the companies in the line.”

Given what we have ascertained from reports of a young Crombie, and the war stories of his notable bravery on the front, it is plausible, although not definite, that Crombie was the officer chosen. Additional, potentially contributing sources to this theory, include an exert from an Epsomian article printed just a few months after Crombie’s death. This article, although incorrect, stating Crombie was at Vimy Ridge when he was not, does mention he was mortally wounded ‘by machine gun fire’ whilst ‘patrolling by night.’ By cradling these operational orders, we can create a possibility for the nature of Crombie’s death. The area this patrol group were to occupy was the ‘Old British support line’ in the ‘spoil bank sector’ near the Belgium village of Zillebeke. Perhaps a night patrol took place here which escaped official recording, and Crombie’s silhouette was spotted in the glistening night air, meaning he was caught in a volley of machine gun fire. We do know however, that the moment of wounding did not cause instantaneous death as Crombie was alive after the incident. Crombie was rushed through the ‘casualty evacuation chain,’ to receive treatment. Post point of injury infliction, stage one of the evacuation process was attention and collection from stretcher bearers, secondly, attention from the medic at a regimental aid post. Thirdly, transport via motor ambulance to a casualty clearing station (CCS). Next, if it was deemed you held a greater chance of survival you would receive medical care here to stabilise your condition, then transferral to a hospital train to finally arrive at a base hospital for more long-term, socialist, care if required. Crombie made it to a CCS. It is most likely he would have got here within 24 hours, perhaps a little longer if a major delay plus considering he may have been injured during the night.

What really happened to Crombie from mid-May to early June, we will never know. Imaginably, nurses clenched sodding rags dragging away the dirt and mud from his face and tore away his tattered tunic no doubt stained with his clotted blood to attend to his wounds as the doctor survived on adrenaline to urgently help his patient. Tragically, nobody could save him; Crombie died at no. 17 CCS (Lijssenthoek) on July 2nd, 1917 just a few days after his 20th birthday.

If we adopt the newspaper date and possible scenario of his wounding, it would have been likely Crombie spent around 4 or 5 days at the CCS before his death, meaning medical staff either felt his condition was stable or knew he was not likely to survive, reflecting on why he did not move further up the evacuation chain. Perhaps Crombie succumbed to infection, spending the last couple days of his life bed-bound and delirious.

Crombie was buried in the adjoining cemetery, where he remains to this day.