Lieutenant Vivian Charles Woolfe Sutton

SN: 2/20th London Regiment (Blackheath and Woolwich)

Case file written by Ellie Grigsby

“God Bless our splendid men

Send them home again

God Bless our men

Send them victorious

Patient and chivalrous

They are so dear to us

God Save our men.”

“I, Vivian Charles Woolfe Sutton swear by Almighty God, that I will be faithful and bear allegiance to his majesty King George the fifth, his heirs and successors, and that I will, as in duty bound, honestly and faithfully defend his majesty, his heirs, and successors in person, crown, and dignity against all enemies according to the conditions of my service.”

On the 7th September 1914 inside Armoury House Finsbury, a young man of 18 years of age, standing tall at 6ft 3 inches, poised with his right arm extended into the air, verbally contracted his allegiance on attestation to King and Country by reciting these words to the recruiting officer on duty. Sutton, once a ‘Mertonian’ and former Rugby School attendee, went on to have an extraordinary military career. Serving primarily with the 2/13th London Regiment (Kensington) and later the 2/20th Regiment (Blackheath and Woolwich) after being commissioned as a temporary Lieutenant, Sutton’s war service took him to Ireland, France twice, Greece, Egypt and Italy.

There are two especially noteworthy chapters of Sutton’s Great War service, including his first theatre of war, which was actually at home and secondarily, finding himself on the Macedonian front.

Sutton and his battalion landed at Cork for security duties following the Easter Rising in April 1916, later moving to Ballincolling and Macroom. The 1916 Coup d’état, fought by the Irish republicans, that sought to dissolve British rule over Ireland was instrumented with the declamation of the new Irish republic on the steps of the GPO on April 24th. With key locations seized around Dublin, the rebels prepared themselves for what was to be heavy bombardment by the angered British Army. Violent fighting in the streets, heavy casualties on both sides, civilian injury and deaths, (the youngest victim at 22 months old) architectural damage, and nationalistic protest mirrored what was happening in France while the First World War waged on and the British army and her dominions prepared for the ‘big push’ which was the contentious and notorious battle of the Somme. Embittered public opinion and absent moral support for the rebels was wide-scale. This was because the majority of people both in Ireland and Britain, sympathised with what horrors their fathers, husbands and sons were facing on the Western Front and felt that nationalistic protest against Britain during this phase of the war was an unforgiveable betrayal. What is essential to appreciate, is, the ‘war effort’ meant something different to everybody; individual’s motives, aspirations, and hopes for the future which fuelled their partaking in the First World War cannot and should not, be generalised to simply ‘defeating the imperialist enemy.’ To many nationalists in Ireland, the enemy was Britain and her sovereign presence over Irish people who felt they deserved to bask in their own cultural practice, govern their own people, trade, and run businesses at home without British intervention. To many, the First World War was the perfect time to hit Britain while she was down. Although the rising was suppressed by the British Armed forces in less than a week, the rebel executions and consequential aftermath is considered by many in historiography as the major turning point in turbulent Anglo-Irish relations. The uprising was quashed on the 29th April, the day Sutton played a role in a controversial war time phenomenon that added a caveat to the multi-dimensional term the ‘war-effort.’

By mid-May 1916, Sutton sailed from Rosslare to fish guard and then returned to Sutton Veny, Wiltshire. By June 21st Sutton was serving in France, until he moved on to arrive in Salonika (now Thessaloniki, Greece) on the 19th November 1916. In terms of military forces engaged of the entire war, the Salonika campaign, between 1915 and 1918, was perhaps the most diverse. British troops, like Sutton, were part of a multi-national allied force fighting against the Bulgarians and their allies in the Balkans. The campaign began October 5th 1915, when one British and two French divisions landed at the port of Salonika, in neutral Greece. The allied troops had been sent in attempt to deter Bulgaria from joining an Austro-German attack on Serbia. The allies had been invited to land by the Greek Prime Minister Venizelos, but he actually fell from power almost at the time when the allied forces stepped ashore. At this time there was a divisional crack through Greek politics, one that would blight the country for decades to follow; therefore, allied forces now faced a potentially hostile government in Athens while trying to organise ways to support their Serbian ally. By late October 1915, the allies were in Southern Serbia, trying to maintain contact with the retreating Serbs who were at that point beginning to crumble under pressure from the central powers’ armies. The Serbs could no longer defend their country and retreated across Albania in sub-zero weather conditions. Known as the ‘Great Retreat’ or simply ‘1915’ in Serbian collective mournful memory, an entire country, government, army, parliamentary deputies, journalists, theatre actors, writers, and thousands of civilians, retreated and then left the country before the invading enemy. The fear of reprisals was such that thousands of young boys were also sent out of the country with the intention of creating a new Serbian Army that would go back to the country and liberate it from the enemy. Some hundreds of thousands died from frostbite, but the survivors were rescued and taken by allied warships to the island of Corfu. Here, the Serbian army recuperated and reassembled.

The victorious Bulgarian army now focused its attention to the presence of allied forces in Southern Serbia. Once again, in heavy snow, on December 7th, 1915, elements of the 2nd Bulgarian army smashed into the Irish divisions’ line on a fog shrouded battlefield and within two days of intense fighting the Irish were pushed back by weight in numbers. Within a week, all British and French forces were pushed back onto Greek soil, heading for Salonika. Apparently, much against British wishes, allied war leaders decided to maintain a military force in the Balkans to establish and secure Greek neutrality mainly, and to try and encourage loyalty of Romania. Thus, British and French soldiers spent 5 months building fortifications in Salonika incase of a Bulgarian attack. These defenses stretched from the mouth of the river Vardar to the village of Stavros on the Egyptian sea. Nicknamed by the British the ‘bird cage line,’ the entrenched positions with machine gun posts and concrete pillar boxes were protected by miles and miles of barbed wire. Within months, Salonika was transformed into a vast military encampment, which was exactly what Sutton would have arrived to, just under a year later. Throughout the campaign, Salonika would remain the main supply base for the allied force in the Balkans because of the port location. The allied forces eventually moved north towards Doiran and spread out, establishing a front line off around 250 miles in length. Holding the allied line with 600,000 soldiers with contingents from Britain, France, Italy, Russia and Serbia, in the French and British contingents were colonial soldiers from India, North and West African and Indo-China, later to be joined by the Greek’s own army, the national defense corps. The allied enemy: the battle hardened Bulgarian army, was well equipped to fight a modern war due to the Balkan wars of 1912/14 and being well supported by the Germans and some Turkish and Austro-Hungarian forces. In the autumn of 1916, the allies launched an offensive which culminated in the capture of Monastir on November 19th. This victory brought the Serbian army back on home soil for the first time in over a year but it was by no means the end of this theatre of war. As lack of man-power and ammunition ensured the Bulgarians would not be pushed back from their man positions along the front, a stalemate set in.

The western front in comparison to the Macedonian front was very contrasting and for men like Sutton to land on Greek soil yet a war zone, it must have felt very strange. Unlike the Western front where man power, equipment and ammunition must have seemed as though it was available in endless supply, on the Salonika front, commanders were forced to conserve resources for large scale offensive actions. This meant the front had to be kept unobtrusively quiet for extensive periods of time. At its peak, the British Salonika Force (BSF) in spring 1917, numbered around 228,000 military personnel. However, the BSF was always inferior to her enemy in numbers and power. Active military activity on the Salonika front fascinatingly and strictly adhered to the weather. Due to the extremity of climate in the summer and winter months, fighting was constrained to the spring and autumn, reflected through choice of time to launch the two major Doiran campaigns of 1917/18. During the bleak winter months, quite like when Sutton arrived mid-late November 1916, he would have felt the bone chilling Vardar winds, attempted to shield himself from the freezing rain and blizzards and most definitely have had regular ‘feet inspections,’ and been given whale oil to rub on his feet while instructed to change his socks regularly in attempt to avoid the debilitating and painful frost bite that was a colossal problem amongst the forces in Salonika. Keeping the army supplied under such treacherous winter conditions proved problematic as the few decent roads in the area collapsed under the weight of the constant use of motorized transport. This meant the only secure way for men like Sutton to receive his rations, ammunition and send letters was via pack mule. Completely juxtaposing the winter, the summer months were equally as perilous as malaria amongst both sides of no man’s land was rife. French General Louis Franchet d’Esperey was charged with drastically breaking the now desperate stalemate on the Macedonian front and that was exactly what he achieved.

The blueprint, to cease the key Bulgarian railheads, 35 miles behind the front line was the key. Taking these two strategic points, would dislocate the Bulgarian rail network all along the Salonika front which would mean trickle by trickle supplies and necessities of the men of the Bulgarian and German army would fade to non-existence and be forced to pull back. So, French and Serbian soldiers attacked into the Balkan Mountains on the 15th September 1918, and within four days had punctured the Bulgarian lines and were moving into the plains beyond. As the German and Bulgarians tried to stem the allied advance, Greek troops waged the second of the Doiran campaigns to prevent any Bulgarian troops swooping west of the Vardar River to combat the French and Serbian advance. 7103 allied casualties were suffered, despite little gain. However, the cunning plan to contain the Bulgarians superseded territorial gain and this came to fruition. Not one Bulgarian soldier moved west of the Vardar River to counter the main allied advance. On the 21st September, British soldiers at the Doiran found the Bulgarians has abandoned their positions and were indeed in retreat. The newly formed RAF bombed and machine gunned the retreating Bulgarians and it was soon a rout. Broken vehicles, dead horses and smashed equipment on the streets signaled victory was in sight. Unable to stop the allied advance, with their army disintegrating day by day, the government called for a ceasefire.

The armistice was singed on the 29th September 1918 and came into force, noon the following day. However quickly these dramatic events in the Balkans faded into un-rememerbed history, purely because of the German armistice soon followed and took its protuberant place in world history, Sutton was a part of an army that fought in a largely forgotten ‘side-show’ of the First World War that should be brought out of the darkness and dutifully remembered.

After just over five months in Egypt, Sutton made his way to Cadet school, (where exactly is unclear from his service record) and after returning to Egypt once more, he was commissioned into the Royal West Kent Regiment on the 18th March 1918. In August 1914, the officer class in the British Army was a small and privileged elite numbering only 15,000 men. During the course of the war, a further 235,000 individuals were given either permanent or, more frequently temporary commissions. One of that 235,000, was Sutton. On the 26th March 1918, he was posted to the 2/20th London regiment, gazetted as temporary Lieutenant. After seeing Italy, Sutton returned to France for the final time. In the interim of this, Sutton was granted home leave from August 14th until September 7th. This was the final time he embraced his mother and father, walked along bustling Sidcup high street, reminded of the calm of pre-war life, and unwound by the fire on those autumnal nights of 1918 in his home: Clare House of Sidcup, no doubt fixating on the emotional strain he was enduring.

Returning to France after leave, Sutton re-joined his men near Harvincourt who were already engaged in an operation since August 23rd, this is his final story.

Orders were received on August 23rd that the men would move out that evening; by midnight, they arrived in billets at Bienvillers. Secondary orders were received before dawn the following morning that the men should be ready to move forward at 07:30am. Slightly later than initially planned, by just gone 9am, the battalion left Bienvillers via Mouchy-Doucy-Ayette. On the nights of the 25th and 26th, the battalion took their positions to occupy south and east of Er Villers. By the 27th HQ and all coys experienced intermittent shelling all-day-long and some battalion casualties were inflicted from gas attacks. As daily reconnoitres were carried out in observation of approaches to Mory, the 29th arrived and orders were received that evening that the battalion must be ready for attack at 5am the next day. At 01:30am on the 30th the battalion were moving to assembly on Mory Beug Natre road. By 04:30am, Sutton’s men were in position anticipating the 5am attack. When the clock struck five, the barrage opened, and the battle commenced. A diary entry at 07:15am ascertains the line was indeed ‘held.’ However, before midday the progress began to change owing to an enfilade of machine gun bullets which forced the battalion to withdraw to their previous position due to the line not being fully consolidated and in good communication with each other. C coy suffered ‘abnormal casualties’ at 13:00pm on the 30th and before 14:00pm intelligence seemed to gather that a counter-attack was imminent. Consequently, two tanks were held in reserve to proceed to the left flank in ready preparation. Later that evening, heavy machine gun fire and relentless shelling, disallowed any advance of Sutton’s battalion. One of Sutton’s comrades, a second Lieutenant Barnes, took out a bombing party along Vraucourt trench at dawn on the 31st to dislodge enemy snipers behind a creeping barrage. Subsequently, 27 died, including one officer, 116 were wounded, 6 were missing but 15 machine guns were captured, 4 trench mortars and 2 rifles. Upon return, Barnes and his men were heavily fired on by machine guns and Barnes was reported wounded and also lost control of the ground gained, however this was regained by the evening. At dusk, further progress was secured at the cost of 17 additionally wounded men, but 5 prisoners were captured and more artillery ceased: the advance continued till the 2nd September.

6pm, September 2nd 1918, five days before Sutton’s leave would culminate, word was reached that Sutton’s battalion would be relieved on the front. But, one hour later, fate transmuted and the previous warning orders were cancelled meaning Sutton’s battalion had to remain stationary. Until the 8th, the battalion obsessively fixated on meticulously planning and perfecting attack enactments, with platoon demonstrations, officers attending lectures, and training in aspects such as bayonet fighting, gas drills, smoke use, and specialist training was also given of Lewis gunners, signallers and bombers. On the 7th, as Sutton prepared to leave home and say goodbye to his loved ones to return to the front, his men were all having a 7am bath. By the 11th, Sutton’s battalion proceeded to Harvincourt Wood, positioned in the south west corner by 23:00pm that night. The following day advances were made following an attack on Harvincourt, only to retreat backwards to the original position by 19:45pm that night. Reconnoitres were ordered for a ‘sampling’ of places to attack on Kimber trench and triangle wood, essentially looking for weak spots to infiltrate. On the 14th September, a ‘zero hour barrage’ opened and all objectives were captured. Consequently, heavy shelling by the enemy followed and by 16:30pm the count-down began to tick as Sutton was soon to lose his life to the First World War. At half past four, the enemy penetrated the allied line and was diverging out. ‘The West Yorks moved up to provide close support’ to B coy on the left flank of the line but grave damage was already done. Of other ranks, 101 were wounded, 18 were killed, 1 was missing believed killed, and 15 were unaccounted for. Among this destruction, was the severely wounded, Vivian Charles Woolfe Sutton.

In Sutton’s service file, the only medical treatment he appeared to receive prior the attack near Harvincourt, was in August 1916, for tooth decay. Amongst the existing primary material, The National Archives holds a hand written letter from Sutton’s father, a C R Arnold Sutton. Received by the war office on the 3rd October 1918, Sutton Senior is imploring the War Office for his son’s death certificate, nearly three weeks post his passing. The only detail given of Sutton’s wounding, in the battalion’s war diary, is an entry on September 14th 1918 which is abruptly revealed as: ‘Lt. C V Sutton wounded.’ Dispassionate by its official nature, this minimalistic evidence is the final commentary we have on Sutton’s life while his heart was still beating. A centenary has passed and it becomes challenging to appreciate the gravity of what was being lost that day with Sutton near Harvincourt with so little words. It is not until you hold the original telegram that was sent to Sutton’s mother and father, held at The National Archives, to affirm his death, does this change. Telegrams fell like leaves in an autumn gale, each one carrying the seed to destroy a world, passed hand to hand gathering darkness as they travelled to a certain destination. Grasping the very sheet of paper Sutton’s father not doubt clutched to with the immense disbelief he had lost his son forever, feels electric, as we suddenly envisage the extraordinary, and what would now seem inconceivable experiences, Sutton endured up until the moment of his death inside that field ambulance. We can we feel a little closer to this family and imagine how they felt when they learnt their beloved son would never return.

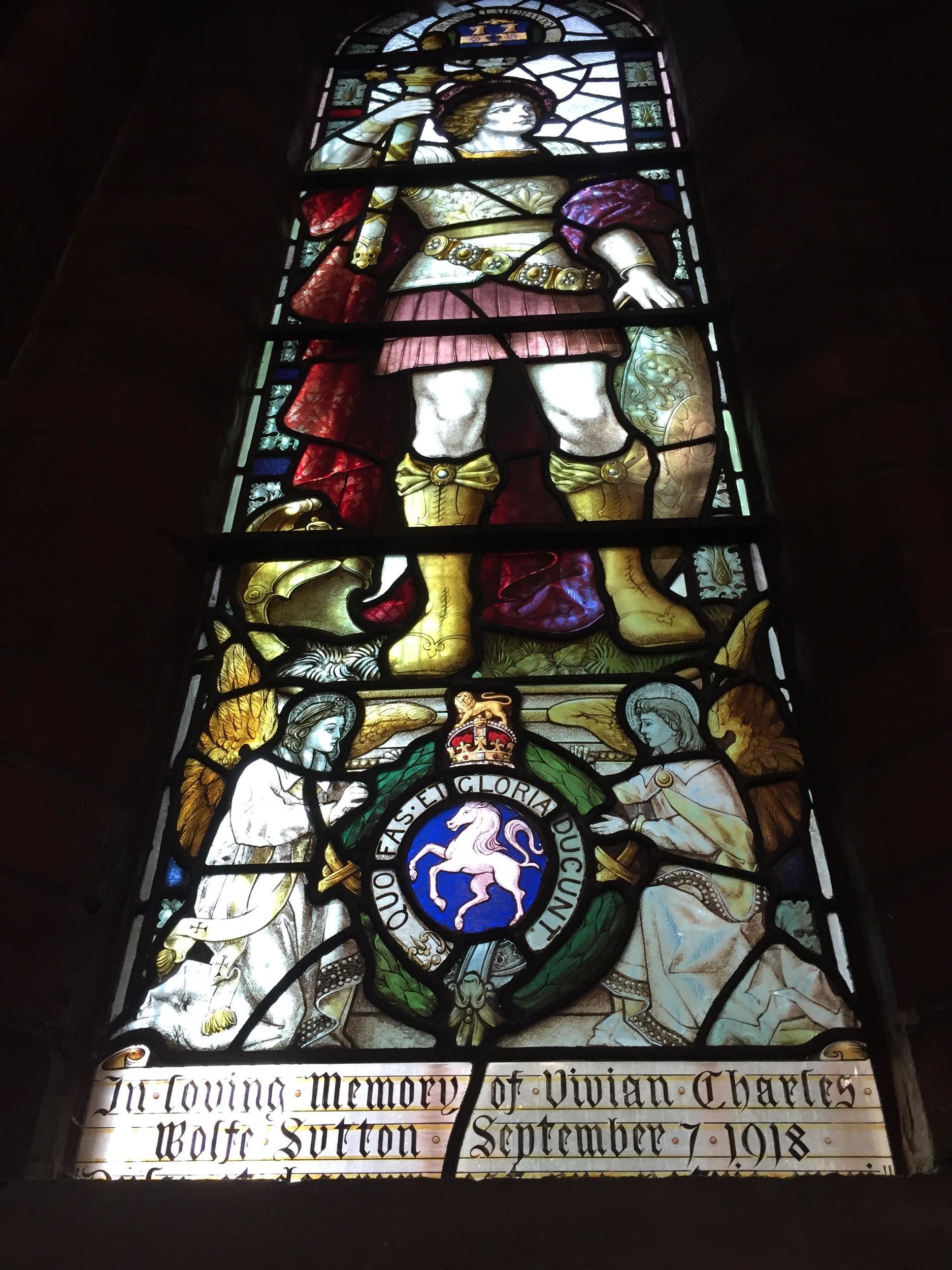

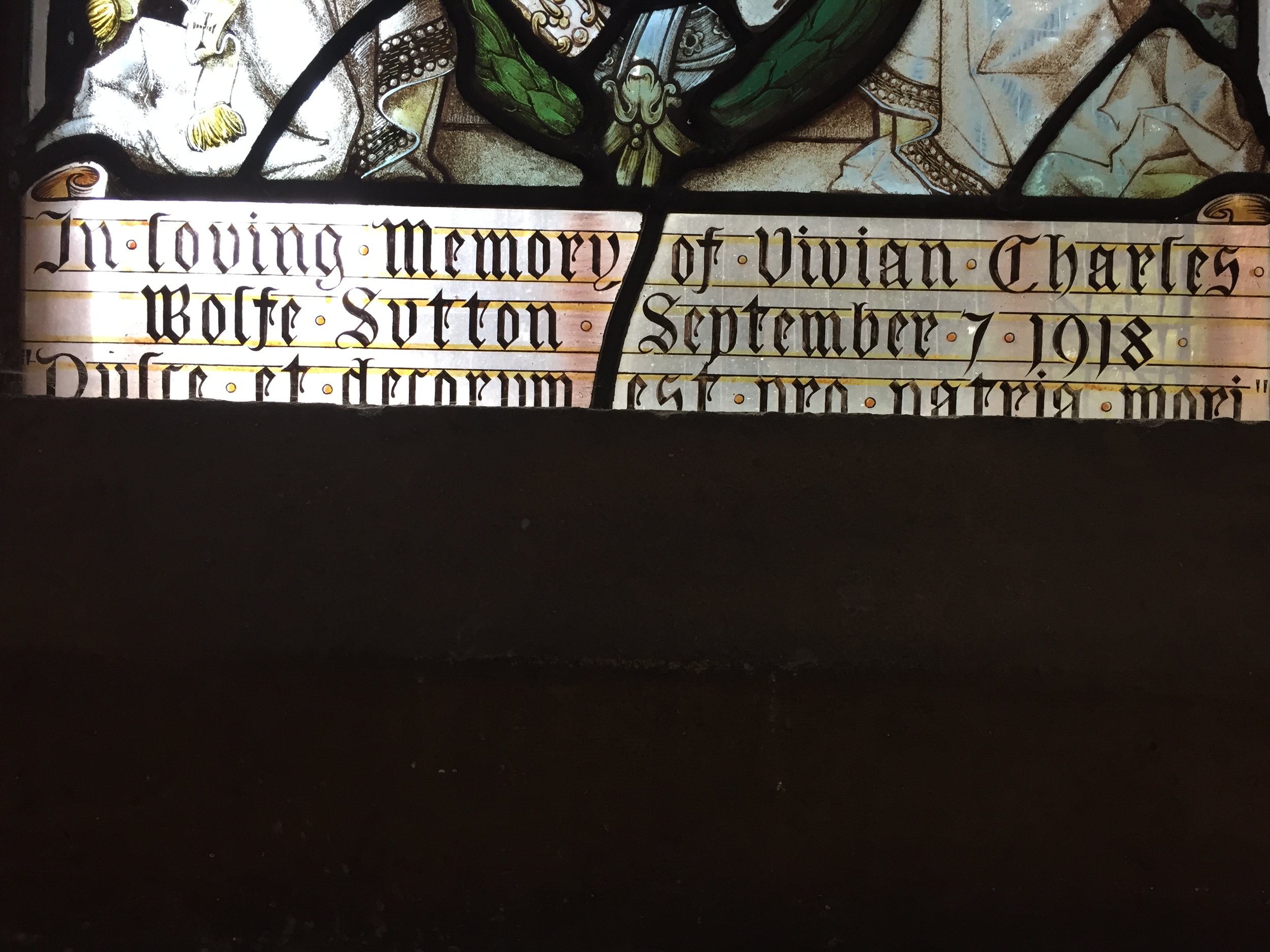

Stained glass window at St Johns Sidcup dedicated to Sutton